Thai Cambodian Conflict

- Al Johnson

- Aug 2, 2025

- 13 min read

A Modern War with Deep Roots in a Colonial Past. NOTE: An excellent overview of the current “Routes and Resources” that are also driving the current conflict, I recommend Michael Yon’s Substack article: Jai Yen: Thailand and Cambodia War of Dissolution for a look at the geopolitical forces at play in the region.

SUMMARY:

The fundamental roots of the Thai-Cambodian border conflict trace back to a period in Thai (then known as Siam) history when it lost between 70% and 80% of its territory to Britain and France during their imperial expansionist campaigns in Southeast Asia. By the early 1800s, Cambodia was a small tributary kingdom of Siam. France, acting arbitrarily and with intentional expansionist goals, signed a "protectorate" treaty with King Norodom of Cambodia in August 1863, gradually reducing Cambodia to puppet-state status over the next few decades. During that time, France continued to expand into Siamese territory, first by forcing Siam in 1867 to renounce all claims to suzerainty over the Cambodian kingdom in exchange for French promises that the Battambang and Siem Reap territories would be recognized as Siamese. These promises were rapidly broken, as gradual expansion from 1886 to 1896 saw the French taking all Siamese territory up to the west bank of the Mekong River, including Sibsong Chuthai, Huapan Tangha Tanghok, and the territory of Laos. In 1907, France "officially and unilaterally" drew the lines of the map for French Indochina and imposed borders upon Siam.

These French occupation maps were challenged in the 1930s by the new constitutional monarchy of Thailand (under the Khana Ratsadon party). The French ignored requests for discussions on adjusting the territory along internationally accepted legal lines. In 1940, when France fell to the Nazis and its overseas occupied areas were administered by the Nazi-aligned Vichy French, the Thai government again requested negotiations. The Vichy French responded by bombing border towns in Thailand. Unlike earlier governments that buckled under French and British pressure, the Khana Ratsadon-led Thai government fought back, and the Franco-Thai War began. The Thai military and Border Patrol Police counterattacked and quickly gained territory in French-occupied Indochina. The Japanese, who had occupied northern Indochina earlier after a brief battle with the Vichy French, exerted pressure on the Vichy colonial government to come to terms with the Thais. Siem Reap, Battambang, and other territories lost to the French from the 1860s through the 1890s were returned to Thailand, with three provinces incorporated into the country.

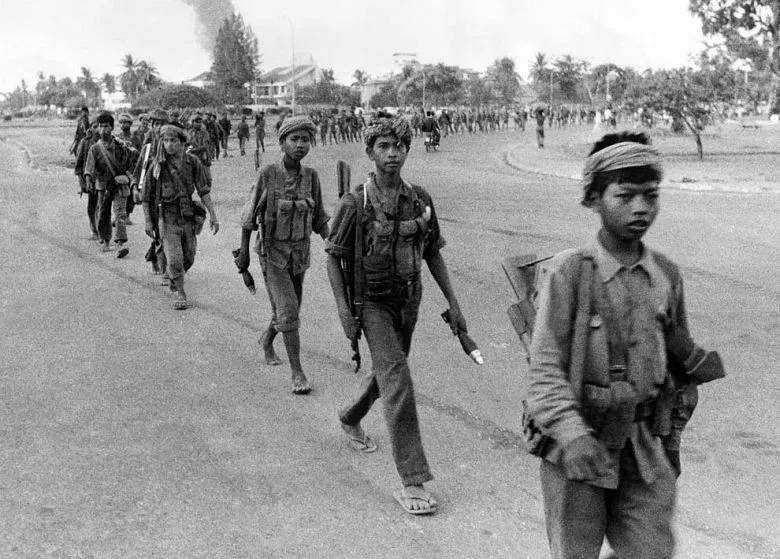

At the end of World War II, the Allies forced Thailand to renounce ownership of the three provinces and "return" them to the French. The French defeat at Dien Bien Phu in 1954 began their withdrawal from Indochina and the "granting" of independence to Cambodia. Thailand reduced its claims for returning territory and opened negotiations on a series of temples along the border. However, in two decisions, international courts sided with Cambodian claims in what many Thais and foreign observers viewed as a legacy of colonial influence. Cambodia maintained a stable government until the rise of the Khmer Rouge, led by French-educated communists who merged communist philosophy and political violence with the Issarak concept of racial nationalism. This formed a Khmer supremacist movement that resulted in a takeover of Cambodia in the 1970s and the second-largest modern genocide in Asia (the largest being the CCP-led ongoing genocide in their occupied territories).

The United States, Thailand, and the CCP strangely supported the Khmer Rouge after 1979 in one form or another. The US and Thailand gradually withdrew support, and the CCP continued to back the KR. Only the Vietnamese government opposed the Khmer Rouge, due to its stringent anti-Vietnamese policy and campaigns into areas claimed by Vietnam. The rekindling of ancient animosity between the Vietnamese and Khmer erupted in Vietnam's invasion of Cambodia from 1977 to 1989, aimed at eradicating the Khmer Rouge. When Vietnam finally withdrew its occupation forces in 1989, the new Cambodian government incorporated many former Khmer Rouge leaders. Thailand initially welcomed the new paradigm and began trading relations with Vietnam and Cambodia—a move criticized by the United States and the CCP.

Another factor to consider is the connections between the Shinawatra clique in Thailand and the current Cambodian ruling clique. These connections developed along personal and for-profit lines, ignoring the population's needs and national security.

During the 1990s in Thailand, the oligarch Thaksin Shinawatra—who built an economic empire by developing the cell phone industry in Thailand—founded the now-outlawed Thai Rak Thai (TRT) party in 1998 and eventually maneuvered his way to become prime minister in 2001. When he was deposed under corruption charges on September 19, 2006, he fled to Cambodia, where he received shelter and was even appointed by Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen as a "special economic advisor." This special relationship with Cambodia's ruling oligarchy lasted through his exile and eventual return to Thailand. However, lately there has been a public feud between the two over Taksin’s inability to “control” his family. Time will tell if this is Kayfabe or real.

His sister, Yingluck Shinawatra, became prime minister from 2011 to 2014 but was also deposed and convicted of corruption. She fled the country and remains in exile. Thaksin's youngest daughter was recently the prime minister but was removed after a phone call leaked in January 2025 between her and family friends in Cambodia's Hun Sen ruling family. The call revealed that Paetongtarn Shinawatra was supporting the Cambodian government against Thai interests and advising the Cambodians to ignore complaints from Thai generals. Thaksin returned from exile to Thailand to face his punishment in exchange for allowing his daughter to become prime minister. Many Thais believe Thaksin partially engineered the current conflict to promote his agenda.

The Shinawatra clan has longstanding and continuing ties to the CCP and its front businesses and Cambodia. Cambodia itself has fallen—like Burma—into an almost tributary state of the CCP.

HISTORICAL DETAILS:

I. Cambodia:

1857–1863: French Expansion into Vietnam and the Targeting of Cambodia

Starting in July 1857, Emperor Napoleon III—using attacks on French missionaries in Vietnam as a "casus belli"—ordered Admiral Charles Rigault de Genouilly to attack and occupy the port of Tourane (now Da Nang) with 14 French ships. This was the admiral's second raid on Tourane, following an earlier one in 1847 to suppress resistance to French missionaries among the Vietnamese.

The French captured Tourane in September 1858 and attempted to move their fleet upriver to seize the city of Hue. Shallow rivers prevented the fleet from advancing, so the admiral turned south and attacked Saigon, capturing it on February 17, 1859, with assistance from Spanish forces. The French tried to hold their positions and force the Vietnamese surrender, but resistance continued until June 1862, when Vietnam ceded three provinces surrounding Saigon.

The French continued their conquest, adding five more provinces in 1867 to form the occupied territory now named "Cochin-China."

During this military subjugation of Vietnam, the French set their sights on the Siamese (Thai) tributary state of Cambodia. At this time, the Cambodian kingdom was much smaller than present-day Cambodia, with much of its current territory belonging to either Vietnam or Siam. The remaining Khmer-managed areas alternated in vassalage between Siam and Vietnam. Cambodia had entered a tributary status with Siam in the final period before French occupation. Seeing a political advantage, the Cambodian monarch sent missions requesting French assistance to remove Cambodia from Siamese influence. France did not negotiate with Siam and declared Cambodia a French "protectorate" in August 1863, signing a treaty with King Norodom.

1863–1940: Gradual Erosion of Cambodian Sovereignty Under French Rule

King Norodom proved naive, believing the French would honor the original treaty. Over the next 20 years, the French increased their control, gradually stripping the king of all sovereignty and reducing him to a puppet.

On June 17, 1884, the Franco-Cambodian Convention forced the Cambodians to accept 11 articles, effectively turning Cambodia into a colony. Among the new rules were the allowance for the placement of French and Vietnamese in major cities outside of control or regulation of the Cambodian government, taxation regulations that favored the French colonists, and allowed the French to purchase any land as "private land" from the kingdom facilitating the purchase and ownership away from Cambodian governing of large French plantations.

October 17, 1887, marks the date when the French gave up all pretense of recognizing Cambodia as a sovereign or quasi-independent nation, violating the original protectorate treaty of 1863. The "Union Indochinoise" decree unified the French territories of Cochinchina (a direct colony), Annam, Tonkin (both protectorates in what is now Vietnam), and Cambodia (also a protectorate) under a single administrative federation headed by a French Governor-General based in Hanoi. This union was not initially a complete political entity but an administrative framework designed to streamline French exploitation of resources, labor, and trade across the region. The French Governor General had dictatorial powers as he held supreme legislative, executive, and judicial powers, appointed by the French president and the Ministry of Colonies, which centralized decision-making far from local rulers.

The new decree meant that the French now outright controlled all of Cambodia's federal budget, customs, public works, and internal security.

A French résident supérieur (resident-general) in Phnom Penh acted as the de facto ruler, with powers expanded by the 1884 convention to issue royal decrees, appoint officials, collect taxes, and manage justice. This effectively reduced King Norodom (r. 1860–1904) and his successors to puppet figureheads focused on ceremonial roles like patronizing Buddhism.

By 1897, French reforms further integrated the Cambodian bureaucracy, favoring ethnic Vietnamese administrators imported from Cochinchina and Annam. This marginalized the Khmer elites and created ethnic tensions, as the Vietnamese and Khmer had been historical enemies with generations of conflict.

1940–1941: Japanese Occupation and the Reversal of Colonial Fortunes

On June 22, 1940, when France surrendered to the Nazis, the governance of Indochina and Cambodia fell under the Nazi-aligned Vichy French government.

In September 1940, the Japanese presented demands to Vichy Governor-General Admiral Jean Decoux, seeking to station troops in northern Indochina and take over operations at the port of Haiphong. They aimed to interdict supplies of arms and munitions smuggled through northern Indochina along the Kunming-Haiphong railway to groups prolonging the war between Japan and the Kuomintang faction in China.

The Vichy French faced a reversal of their colonial maneuvers from less than a century earlier, confronting invasions from both the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA)—under the 5th Division commanded by Lt. Gen. Nakamura Akihito—and the Chinese Kuomintang Nationalist Army, most likely led by Yunnan Governor Long Yun. The KMT staged a brief invasion from the north but was repulsed by Vichy French forces. The Japanese began occupying northern crossings, but fighting broke out as the Vichy French accused them of violating the agreement. The Japanese quickly defeated the Vichy French and advanced through Indochina. From then on, the Japanese dictated terms, allowing the Vichy French to administer Indochina while maintaining Japanese political primacy to secure their national interests until the Second Sino-Japanese War concluded.

The Japanese military initiated communications with Cambodian independence leaders. While junior officers were supportive, higher headquarters prioritized maintaining the status quo and discouraged schemes to back Cambodian independence or restore an independent monarchy.

1941–1953: Wartime Shifts, Japanese Coup, and Post-War French Return

As Vichy France's days appeared numbered toward the end of the war in Europe, the Japanese uncovered various schemes by Indochinese French governors to attack them. The Japanese launched a preemptive strike in March 1945, capturing most French governors and assuming direct governance of Indochina and Cambodia. For Cambodia, this renewed the possibility of regaining status. With Japanese support, King Norodom Sihanouk proclaimed an independent Kingdom of Kampuchea using the old Khmer language.

The Allied victory in WWII meant the French colonial occupation resumed, and King Sihanouk quickly acquiesced to French demands, reverting to puppet status. However, in 1953, he positioned himself at the head of the Issarak independence movement. On November 9, 1953, under international and internal political and economic pressure, France relinquished control of Cambodia and "granted" it independence.

However, the territory France gave to Cambodia included large parts captured and occupied by Siam (Thailand) in the late 1800s and early 1900s—territories Thailand had reclaimed in 1941 but was forced to relinquish after World War II.

II. Siam (Thailand)

Mid- to Late 1800s: Facing Colonial Pressure from Britain and France

In the mid- to late 1800s, Siam faced increasing pressure from Britain and France, both of which had expanded their influence in Asia by defeating regional powers such as Burma, Vietnam, Annam, multiple Malay kingdoms, India, and the Manchu Empire.

In 1855, Britain negotiated the Bowring Treaty with Siam, which granted extraterritorial rights to British subjects, fixed import duties at 3%, and ended royal monopolies on trade, including restrictions on opium imports. This shifted control over customs, taxation, and judicial matters involving British subjects to Britain. Further treaties in 1874 and 1883 extended British influence over northern forested areas around Chiang Mai, allowing British logging operations. Siam lost effective management of these resources, with teak—a key export—coming under British control, and imported workers from British territories receiving preferential legal status.

Siam also experienced territorial losses in Cambodia and Laos. France pursued more direct expansion compared to Britain's economic-focused approach.

1893–1909: Territorial Losses to France and Britain

In 1893, tensions over the Lao territories escalated into the Franco-Siamese Crisis. Siam sought to assert control, hoping for British support against its historical rival, France. When Britain did not intervene, French gunboats blockaded Bangkok and clashed with Siamese forces at Paknam, while French troops occupied Chantaburi. Siam signed the October 3, 1893, treaty, ceding Laos east of the Mekong River and establishing a 25-kilometer demilitarized zone on the west bank. Subsequent treaties in 1904 and 1907 further ceded territories, including Battambang, Siem Reap, and Sisophon, in exchange for the withdrawal from Chantaburi and Trat and other concessions. In 1909, Britain negotiated the Anglo-Siamese Treaty, acquiring four southern provinces—Kedah, Kelantan, Perlis, and Terengganu—in exchange for abolishing extraterritoriality and providing a loan.

1932–1939: Revolution and Diplomatic Challenges

In 1932, a group of military officers and civilians—many educated in Europe and influenced by French democratic ideas, British constitutionalism, and Sun Yat-sen's Kuomintang principles—staged a bloodless coup, transitioning Siam from an absolute monarchy to a constitutional system. They formed the Khana Ratsadon party to modernize the country and achieve parity with Western nations. The name "Siam" was changed to "Thailand" in 1939, emphasizing "Thai" (meaning "free"). Having supported the Allies in World War I and participated in the League of Nations, Thai leaders sought diplomatic recognition of their territorial claims against France but proceeded cautiously.

1937 during Mekong River navigation talks, Thailand proposed a midpoint boundary in line with international standards, but France maintained control over the whole river and the west bank. As Europe approached war, France sought a non-aggression pact with Thailand in 1939. Thailand reiterated its territorial requests, including Mekong navigation rights, but France declined. In March 1940, both sides agreed to a commission to review border issues.

June–November 1940: Fall of France and Escalating Tensions

After France surrendered to Germany on June 22, 1940, Thai Prime Minister Plaek Phibunsongkhram expressed concerns to British Ambassador Crosby that Japan might occupy French Indochina, prompting Thailand to pursue territorial recovery beforehand.

On August 15, 1940, Thailand consulted the British, Italian, American, and German ambassadors in Bangkok regarding potential demands on France, separately engaging Japan. Italy and Germany supported Thai claims, Britain urged restraint, and US Ambassador Hugh Gladney Grant opposed the idea.

In September 1940, as Japan pressured Vichy France in northern Indochina, a Thai delegation in Saigon proposed a mutual defense pact against Japan in exchange for territorial returns. France rejected the offer. Japan's victory over Vichy forces on September 22 and the Tripartite Pact with Germany and Italy on September 27 strengthened Japan's regional position. On September 28, Thailand initiated formal talks with Japan for mutual assistance, securing assurances of non-opposition to Thai claims in exchange for base access. By October 15, Japan agreed to mediate, though Thailand also explored British options in Singapore.

By November, with mediation stalled, Thailand leaked intentions of a British defense pact to prompt Japanese action. On November 20, Japan committed to mediation but sought to limit Thai claims in Indochina, suggesting a focus on British Malaya instead. Vichy France initially rejected negotiations.

Britain explored U.S.-British mediation, informed by a French naval officer's visit to Singapore, but the US State Department declined involvement.

January–May 1941: The Franco-Thai War and Settlement

Japan provided Thailand with military equipment amid escalating border incidents. Following mutual skirmishes, including French aerial bombings, Thailand launched a ground offensive into Indochina on January 6, 1941.

Thai forces advanced in Laos and Cambodia, outperforming expectations against Vichy troops despite being outnumbered in some areas. The army repelled counterattacks under challenging conditions. The Thai Air Force flew both American and Japanese aircraft against the Vichy French forces engaged in dogfights, close air support, reconnaissance, and bombing.

One account of an engagement on the 28th of January states “On 28 January, nine Ki-30s, four Curtiss Goshawks, and three Martin 139's, the latter escorted by three Curtiss Hawks, were dispatched to bomb Siem Reap. This vital French airfield near the temple of Angkor Wat was one of the largest of it's kind in Southeast Asia. Coupled with sorties against Pailin and Sisophon on the same day, the raid on Siem Reap would be the last of the Franco-Thai War. Several French aircraft were destroyed on the ground and vital hangars and repair facilities were made inoperable. One of the Ki-30's piloted by Wing Commander Fuen was photographing the effectiveness of the bombers when he was intercepted by a pair of Moranes that had scrambled to the defense of the base despite the carnage on the runway. A near-comical chase ensued between these three aircraft. Making multiple passes, the Moranes expended both of their twin 7.7 machine guns without even scratching the slow and clumsy Nagoya. The French pilots then simply waved goodbye as they passed Wing Cmdr. Fuen.” - From https://warfarehistorian.blogspot.com/2020/01/franco-thai-war-indochinas-micro.html

However, the Thai navy didn’t fare so well. On January 17, 1941, Vichy French warships engaged Thai vessels off Ko Chang. The French sank the coast defense ship Thonburi and torpedo boats Songkhla and Chonburi. Still, Thai air support damaged French ships, forcing their withdrawal and turning the engagement into a tactical draw.

Japan mediated an armistice, and negotiations followed. Vichy France, facing supply shortages and military setbacks, agreed to concessions in a Japanese-mediated protocol signed on March 11, 1941. This plan provided for the return of the west bank territories and a substantial portion of northwestern Cambodia, but not the town of Siem Reap or Angkor Wat, while setting the Mekong boundary at mid-channel (with two islands under joint Thai-French administration). While this marked the pivotal moment of French capitulation, the formal and legally binding treaty—reiterating these terms—was signed on May 9, 1941, in Tokyo. Approximately 68,000 square kilometers (~26,000 square miles) of territory was returned. French citizens in the recovered areas retained rights equivalent to those of Thai citizens. Prime Minister Phibun proposed demilitarizing the border to signal no further claims and ease tensions. 5

However, after the war the US and UK promoted the return of the Thai areas to France. In 1953 Cambodia inherited the Thai provinces. During the reign of King Norodam Sihonouk of Cambodia, the issues were negotiated to both parties favor. However, after the upheaval in Cambodia and moves such as application to the United Nations by Cambodia to recognize contended historical landmarks as “Cambodian” tensions have flared again.

Comments